The work of the courts and the police is subject to strict rules and regulations, with activities that can have huge impacts from an individual to an international level. Facilitating those important duties is a role that Invesis takes very seriously in the range of justice projects it leads.

According to Nicolle McKibben, Senior Project Manager at Invesis, whether it’s a police headquarters or international courts complex, “the authorities are in the great position of having transferred the risk associated with running these big, technically complicated buildings to an experienced third party that’s an expert in doing that. It gives them a lot of comfort that they’re going to have that consistently performing facility that they can use as they need to, and allowing them to concentrate on their responsibilities to uphold safety and justice.”

For Invesis, these projects start well before any design is drawn up because, perhaps more than in any other sector, the importance of getting the practical aspects right from the beginning is absolutely fundamental to the well-being of the users and the strict protocols they are required to follow.

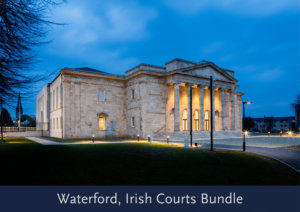

For example, in the €150m Irish Courts Bundle, involving the construction of 31 court rooms across seven courthouse buildings, legal practitioner suites, offices, witness suites, custody areas, archive rooms and Garda (police) rooms, with five of the courthouses incorporating protected structures, there was extensive use of BIM modelling to develop Design Intent Drawings.

As SPV Manager and equity investor, Invesis has worked closely with the Courts Service of Ireland since 2014, undertaking a significant amount of design and development to understand how courtrooms are used.

“User flows”, says Declan Gallagher, Invesis Project Director, “are so important – we considered how the public would enter and navigate the buildings, the judiciary, judges, staff, juries – who could be in the same spaces at the same time, who certainly could not be allowed to interact and how to segregate victims and vulnerable parties.”

He goes on, “We went down to cell areas of other facilities and checked what happens when a prisoner gets out of the van. We asked about incidents and accidents they’d had over the last ten years so we found out all the ‘cheats’ the prisoners tried in the cells and then we designed ways around them.”

This type of attention to detail ensure that everyone who uses or visits the buildings, including children, can be confident of coming into a very safe environment. We know that in other courts, outdated buildings lead to those participating in hearings being crammed into corridors and small rooms, causing regular violent confrontations and making already difficult situations even worse.

The €65m Dutch Supreme Court building houses 350 staff, a reception for 400 people, two cells, meeting rooms, a restaurant, two courtrooms that can accommodate 400 people, a library and an archive. It provides a very different function to a family court, although aspects such as the separation of judges and prosecutors mirror requirements in Irish Courts Bundle. For Philip Kroner, Asset Management Director at Invesis, keeping these types of buildings secure and fit for purpose is, “a lot to do with understanding the processes that apply to their operation.”

This is where the Invesis model of fully integrated design, construction and ongoing facilities management services comes into its own. It incentivises Invesis to get it right at the design stage, incorporating flexibility and future proofing so that operational issues can be minimised.

Turning to the UK, Invesis is also responsible for two landmark Police Headquarter facilities. The €54m Cheshire Police Headquarters accommodates 1,000 personnel in more than 50 departments, and the Derby Police Headquarters houses 450 police officers, 60 civilian support staff and a 39-cell custody suite. Invesis Project Director, Eilidh Paffett, refers to the close relationship needed with the police authorities right from the start; from understanding exactly how things have to work all the way through the operational phase.

Turning to the UK, Invesis is also responsible for two landmark Police Headquarter facilities. The €54m Cheshire Police Headquarters accommodates 1,000 personnel in more than 50 departments, and the Derby Police Headquarters houses 450 police officers, 60 civilian support staff and a 39-cell custody suite. Invesis Project Director, Eilidh Paffett, refers to the close relationship needed with the police authorities right from the start; from understanding exactly how things have to work all the way through the operational phase.

She asserts, “I think one of the beauties of that long-standing relationship is the change process that’s built into our contracts. So, although we have designed and built something sometimes 20 or 25 years ago, we have the flexibility to be continuously reviewing the building and their operations and, if required, the project can be updated or altered in conjunction with our partners.” This adaptability demonstrates that PPP contracts are far more dynamic than commonly perceived, allowing ongoing refinements that meet evolving needs. She goes on, “Police organisations in my experience are extremely dynamic – they have lots of churn, they change their operations frequently, they have consistently evolving teams, they’re always rejigging the way that they do things in response to crime themes, so often they’ll say ‘we need this bit of the building to work differently for us, we need to use it in a different way and that’s where we come in.”

It’s then the job of Invesis to bring the right people together to develop the ideas and deliver the changes. “So,” says Paffett, “although these buildings may have been constructed quite a long time ago, they’ve evolved with the organisations and you have the expertise already there in existing relationships so the work can be done efficiently, effectively and to appropriate standards which is hugely important. It’s paramount that the users are safe because of the nature of the activities that police and justice sectors are working in.”

As a result of the rigidity of the legal processes that courts adhere to, Gallagher confirms that big, structural changes are not so common in Irish Courts Bundle, but one element of future proofing in the design is now coming to the fore in an initiative aimed at saving both money and energy. Partly stimulated by the impact of the Covid pandemic, hearings are now being held with judges and juries in the courthouse, but with defendants remotely located. This means the costs and resources of transporting people from a prison an hour away, to spend two minutes making a plea, before being driven back, are avoided.

As a result of the rigidity of the legal processes that courts adhere to, Gallagher confirms that big, structural changes are not so common in Irish Courts Bundle, but one element of future proofing in the design is now coming to the fore in an initiative aimed at saving both money and energy. Partly stimulated by the impact of the Covid pandemic, hearings are now being held with judges and juries in the courthouse, but with defendants remotely located. This means the costs and resources of transporting people from a prison an hour away, to spend two minutes making a plea, before being driven back, are avoided.

At the outset, each courtroom had panels to which cables could be run and they are now being equipped with screens and digital equipment allowing a link to be established to a prison, so the hearing takes place remotely for the prisoner.

In the 24-hour environment of a police headquarters, with operations running continuously and cells used day and night, Paffett points out the advantages of the close coordination that is undertaken by the Invesis site teams when scheduling lifecycle works with minimum disruption. In fact, the benefits of the ongoing involvement of Invesis to the procuring authority in the operational phase are multi-faceted as it can leverage the experience and economies of scale that Invesis and its partners can access, as well as the local project management teams it deploys.

When it comes to energy management in the Irish Courts Bundle, Gallagher advises that, “we did a lot of work with building management systems, a lot of staff retraining, we changed a lot of timetables, lighting schedules and undertook a lot of reprogramming.” He continues, “we looked at quarter-hourly data to see where energy was being used. We had a weekly, then fortnightly, and now monthly energy meeting with the Court Service where we went through every courthouse and saw peaks and troughs in the month’s energy usage data. If we saw a peak, we’d ask why. We have the staff employed to do these reviews all the time – and we know that not every court outside has access to that additional support and so doesn’t get these benefits.”

When it comes to energy management in the Irish Courts Bundle, Gallagher advises that, “we did a lot of work with building management systems, a lot of staff retraining, we changed a lot of timetables, lighting schedules and undertook a lot of reprogramming.” He continues, “we looked at quarter-hourly data to see where energy was being used. We had a weekly, then fortnightly, and now monthly energy meeting with the Court Service where we went through every courthouse and saw peaks and troughs in the month’s energy usage data. If we saw a peak, we’d ask why. We have the staff employed to do these reviews all the time – and we know that not every court outside has access to that additional support and so doesn’t get these benefits.”

Changes made as a result of the energy trends analysis include lots of small details that add up to a meaningful total of impactful adjustments. They include reprogramming around 30 lifts not to automatically return to the ground floor after use and amending the lighting schedule in the judge’s chambers to reduce the time lights are left on when they leave the room.

Keeping sustainability high on the agenda has led to the installation of electric car charging points at the seven sites of Irish Court Bundle, the rewilding of the green areas, changing all lighting to LED, installing solar panels on courtroom roofs and implementing boiler upgrades.

Of course, any building in which controlled activities take place with legal repercussions demand bespoke structures, but cost and energy saving ideas are regularly shared across the Invesis operational project teams. Those teams can bring improvements to a range of services, generally including building and equipment maintenance, cleaning, catering, security (locking down the building and providing a help desk to manage issues as they arise), accommodation, waste control, including contaminated waste such as syringes and blood, pest control and landscaping.

Of course, any building in which controlled activities take place with legal repercussions demand bespoke structures, but cost and energy saving ideas are regularly shared across the Invesis operational project teams. Those teams can bring improvements to a range of services, generally including building and equipment maintenance, cleaning, catering, security (locking down the building and providing a help desk to manage issues as they arise), accommodation, waste control, including contaminated waste such as syringes and blood, pest control and landscaping.

On a project-by-project basis, Invesis now also commits to identify feasible opportunities to invest in tailored energy efficiency measures. At the heart of all of these efforts are the positive relationships that are nurtured during the design, build and operation of each project, building trust between valued partners in a setting where confidence and security are critical.

Our Contributors:

From Left to Right: Project Directors Eilidh Paffett and Declan Gallagher, Senior Project Manager Nicolle McKibben, and Asset Management Director Philip Kroner.